This week’s article is provided by Paul Gibbons, academic advisor and author. The article is an excerpt from his new book The Spirituality of Work and Leadership: Finding Meaning, Joy, and Purpose in What You Do. It is a companion to his interview on Innovating Leadership, Co-creating Our Future titled Finding Meaning, Joy, and Purpose in What You Do that aired on Tuesday, September 7th.

VOCATION AND SPIRITUAL FIT

“Most people’s jobs are too small for their spirits.” ~Studs Terkel, from Working

People spend nearly half their waking lives at work, perhaps 100,000 hours in a lifetime. In the previous chapter, we argued that the time one spends working should be joyfully and purposefully spent, contributions should be a source of meaning and fulfillment, and social interactions should be a significant source of community and connectedness.

In this chapter, we start with questions about vocation and mindset: Which matters more: what you do, or how you do it? Can you bring a spiritual mindset, say of gratitude or service, to any job? How much responsibility for the worker’s experience lies with the worker, and how much with the employer?

CHOOSING WORK – BALANCING SECULAR AND SPIRITUAL

“Discovering vocation does not mean scrambling toward some prize just beyond my reach but accepting the treasure of true self I already possess.” ~ Father Thomas Merton

One workplace spirituality “killer-app” is vocation choice, sometimes called fulfilling your purpose in life, finding your calling, or “following your bliss.” This subject has birthed hundreds of books. A few, such as Connections between Spirit and Work in Career Development, are academic in approach. Others are more inspirational and practical, such as True Work, The Purpose Driven Life, The Leaders Way, The Work We Were Born To Do, and The Art of Work.

The above books rightly say that the feeling of being called may be immensely powerful. For the called, it may provide motivation to make drastic life changes. Calling provides a narrative for work that can help you soar in the good times and transcend the bad times. It helps leaders lead with greater passion and charisma—indeed, many leadership development programs help leaders create a powerful career narrative about their highs and lows and the learning from those that has shaped who they are. In my programs, leaders used to explore this by creating a timeline of life and leadership experiences that had shaped their vision and values and that shape what is unique about them and what they stand for as a leader.

There is a question of whether calling comes from “out there,” the Universe, a Higher Power, God, or whether (as existentialists would have it) there is no purpose “out there,” but we are liberated to choose for ourselves. Different strokes.

For the existentialists or people without a deity, this freedom of choice, of accepting responsibility for those choices, and of doing the work of creating meaning can be hard. In the words of Jean-Paul Sartre, “Man is condemned to be free; because once thrown into the world, he is responsible for everything he does. It is up to you to give [life] a meaning.”

When reflecting upon your calling, using one of the many guides available, you want first to focus on the spiritual, the meaning derived from work, and on intrinsic satisfaction rather than on skills, interests, job opportunities, financial rewards, and traditional views of success. Secular concerns press upon us all the time, so we give priority to the less urgent but more important. There are various tools career coaches use to help with this: narratives, dreams, symbols, poetry, visualization, and insights from the past.

Once you’ve used these “spiritual tools,” you balance spiritual with secular concerns.

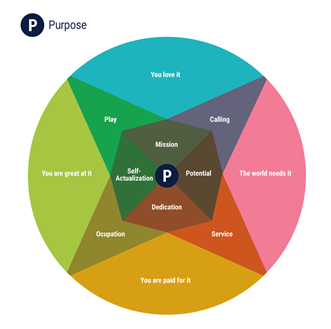

One simple tool, the Ikigai (“reason to live” in Japanese), helps readers think through the tension between the secular and spiritual worlds53.

Diagram V-1: The Ikigai career purpose tool

To use this tool, spend about an hour thinking about each of the petals and the tensions between them. Ask yourself which petal is most or least fulfilling in your current role. (I have formalized this process with a questionnaire and in workshops, but the do-it-yourself approach works well if you dedicate the time to it.)

Where some books on calling are wrong

“If you’re having work problems, I feel bad for you son. I got 99 problems but meaning ain’t one.” ~99 PROBLEMS, JAY-Z , paraphrase

Coaches and self-help gurus sometimes draw a distinction between societal and parental influences, the tangible pressures of living (paying rent), and what the “inner-self” or “real you” or “true self” is called to do.

This distinction is false and unhelpful because there is no “you” bereft of any historical or cultural influences – your likes and dislikes, talents and shortfalls, personality, and values were shaped from an early age by dozens of influences. You can’t untangle the threads and find a “pure you” in there. Humans have many scripts running – you just get to choose which you pay attention to. You also get to choose to set some influences aside and give more weight to others.

We gain information about the world of work as we mature. Sometimes I advise young people that early jobs are as much about finding out what you dislike as what you like. Choosing a career is always a balancing act of dozens of factors including some fairly prosaic geographical ones such as where you prefer to live, where your spouse prefers to live, where the schools are good, where parents, friends, and relatives live, as well as all the different factors covered by the Ikigai.

Another faulty assumption of many spiritually oriented career counselors and coaches is that the practical matters of earning a living, developing skills, and finding a job will “unfold” once finding a calling unlocks the passion and commitment that lie within you. I don’t think this is helpful or true. There is a certain kind of spirituality, usually New Age, that holds that once you find your calling and put your career intentions “out there,” the Universe will provide a living.

Well, as they say in the Middle East, “…trust Allah but tether your camel.” Even though the Universe is on your team, put the hard work in. Circumstances, opportunity, luck, the economic environment, and your job-hunting skills will play a part in the realization of your calling. Adults need to balance passion and practicalities in the world of work – and (again) need to balance secular and spiritual concerns. (There is a 12-Step expression: “God does the steerin’, I do the rowin.’” For Humanists, it might be, “the purpose I’ve created does the steerin’, and I do the rowin.’”)

Another faulty assumption of some spiritual approaches to calling is that finding your calling and doing it is necessarily a source of great joy. Maybe. Life stories of great saints suggest that not everyone who is “called” finds it easy. It sometimes demands great change and sacrifice. You might be called to earn a quarter of what you do now. Or are you ready to uproot your family? Are you ready to go back to school? Do you want to be called to sacrifice? Do organizations want their workers to be called? Typically, in the 21st century, we want the “goodies” from calling or vocation without the sacrifice.

Coaching people out the door

“They attain perfection when they find joy in their work.” ~The Bhagavad Gita

Finally, coaches focus on worker self-actualization for (or so they should even if they are performance coaching), but many times when I’ve coached a mid-career executive on career matters (paid for by the company), they decide to go self-actualize somewhere else. When my firm ran a leadership development program for a few dozen senior investment bankers (partners in a big firm), we talked about choice, self-expression, joy, balance, work-family, and goal setting. Five of our initial group of 12 were gone within a year (retired, began independent consulting, or moved to another firm).

In the long run, empowering self-actualization that leads to someone quitting may benefit the business, creating an opening for someone whose passions may be more aligned. (After all, you should prefer employees who are passionate about being there.) The employee’s departure increases the amount of big-picture happiness in the world—you’ve done a good thing. In the short run, though, it looks like financial folly—investing in executive coaching to watch your employees leave and then incurring the cost of losing and rehiring a worker.

The challenge for businesses is how to improve their recruiting and interviewing processes to better identify those who are truly called to work for them. How can organizations best hone and express their mission so prospective employees can discern whether they should be working there?

There is a bigger challenge we get to later which is how businesses can they make sure their insides live up to the glossy outsides of recruitment pitches.

THE SPIRITUAL FIT

“…you are someone who has a particular passion or a particular personal philosophy, and you’re able to turn work into an instrument of realizing the deeper meaning in pursuing your personal philosophy or passion.” ~Satya Nadella, Microsoft CEO

Satya is talking about what I call the “spiritual fit” how well one’s purpose and values fit with the specific mission of our employer. However, a courtship might produce a fit and result in two people deciding to marry but working on the fit does not stop there. Even if you find a job in the Ikigai sweet spot – that is:

- Work that the world needs,

- Work we are passionate about,

- Work that tests us and uses our skills,

- Work that remunerates us well.

… the “marriage” demands work on both sides. For firms, the fit isn’t just about hiring workers who fit, it is about helping new workers onboard.

Back in the day, even at my blue-chip former employers, the boss “onboarded” new hires, thus: “there is your desk, the bathroom is down the hall, and the coffee machine a bit further.” That is it. There was zero effort to help new hires fit – to help them make sense of the values of their new firm, and how their skills might contribute to their passion and purpose. Our connection to purpose, if it happened, was left to chance.

In the 1990s, PwC offered new employees a whole day onboarding! That whole day was then seen as indulgent by some but would seem ridiculously short to today’s HR professionals – and today PwC’s process is six months long. Leading firms take onboarding very seriously: Google also devotes six months to it, kicking off with an intensive two-week immersion into “being Googly” (the culture) but also the structure and strategy of the business and the architecture of the platform.

Hiring and onboarding help with internal fit. One could recommend companies look more deeply into values and purpose at the recruitment stage, but as values questions become more personal, they may veer into off-limits territory or may be potentially discriminatory. Fits won’t be perfect or permanent – some employees don’t know what job they want until they see it – and at 25, you ain’t seen much. Some jobs look juicy from the outside but don’t feel right once you are in them. (And sometimes, as the song says, “you don’t know what you got ‘til it’s gone”.)

Choosing the right profession and the right company to work for can be a long journey. You have to constantly reassess your priorities, values, fit with your employer, and whether the path you are on is one you value and admire. Mormon, Steven Covey said cleverly, “there is no use racing up the ladder of success if it is leaning against the wrong wall.”

However, I recommend strongly against daily or even monthly questioning of values and fit and purpose in life. I think that is a recipe for misery. Rumination, experts say, is among the unhealthiest psychological habits. The question “Is this the right job or profession for me” is one to be taken seriously, but only periodically – semi-annually, or annually. Once you commit, you stop asking the question for another six or twelve months – when it pops into your head, you set it aside.

Having said that, you should put your values, fit, and purpose to work in daily life – questioning yourself hard on whether you are living up to them. That is the spiritual challenge – not to get too comfortable with yourself, but also having a depth of self-compassion for your stumbles. Few of us can walk in and say “take this job and shove it” without consequences. Daily, you recommit to where you are and to the sorts of attitudes that make you happier and make you a nicer person to work with.

This, clearly, speaks to the necessity of making time for annual (or so) reflection upon your purpose and values – again not ruminating daily, but when the time that you set aside comes, engaging in purposeful life-design (or re-design.) Once, you commit to change, it will still take a long while to enact your new vision or profession. When I coached mid- or late-career people who desired or were approaching a major career transition, I used to advise that such transitions take a year to envision, plan, and execute. If you are retiring from a 40-year career, I suggest (unless your only goal is the hammock) that it takes five years to build up a portfolio of stimulating, enriching service and commercial opportunities.

A final source of misery is people who suffer at work, decide to change, and who fail to take action. They wake up each day with “I need to change jobs” for months or years without acting – getting a little unhappier and a weakening sense of their own power and agency. Usually, they need support in planning and being held accountable for taking the baby steps to realize the change.

This discussion has mostly been about fitting the job to yourself, that is finding work that aligns with your purpose and calling. However, there is another spiritual job alluded to above, fitting yourself to the job with the right mindset.

IT AIN’T WHAT YOU DO, IT’S THE WAY THAT YOU DO IT54

“For works do not sanctify us, but we should sanctify the works.” ~Meister Eckhart

While vocation choice concerns itself with “doing the work you love,” the alternative is “loving the work you do.” In other words, how do you “get your head right”? Which work attitudes and beliefs affect your experience of work? For example, if work is approached as a place of service or giving, rather than a place of being served or getting, would one enjoy it more? Was St. Francis right in saying, “It is better to understand than to be understood, to comfort than to be comforted, to love than to be loved, better to give than to receive”? Is the secret of happiness not doing what one likes, but liking what one does? At one spiritual retreat I spent time with a Benedictine Abbott and even though 25 years ago, I remember his questions: How is life treating you, Paul? More to the point though, how are you treating life?

Meaning making

“Do not indulge in dreams of having what you have not, but reckon up the chief of the blessings you do possess, and then thankfully remember how you would crave for them if they were not yours.” ~Marcus Aurelius

Ancient spiritual texts and modern writers on humanism suggest that taking personal responsibility for meaning “creates the work reality.” Viktor Frankl was able to find meaning in a concentration camp. In the yogic spiritual tradition, the concept of Karma Yoga suggests that working with love and enthusiasm can turn a chore into a spiritually enriching experience. The Buddhist spiritual path (bodhisattva) recommends going forth for the welfare and benefit of the world to prevent suffering. In Hinduism, the concept of right livelihood affects one’s karma, one’s inheritance in the next life. Christian monks maintained “laborare est orare” (to work is to pray). These views suggest that enjoyment of work is “an inside job”—if you can bring the right attitude and actions to work, you can transform your experience of it.

Recall the parable of the stonecutters. The third stonecutter’s narrative was: “I’m creating a magnificent cathedral.” We get to decide which cathedrals we are building by creating our own narratives. This illustrates, again, that meaning isn’t “out there” but is created; it’s created in this case by—the why of our work. Sadly, the prevalent and contrary view in society is that what happens determines what we feel and do: “He made me furious” or, “Work is killing me.” If one’s mood is determined by context, then it will ebb and flow with the fortunes of life. If the actions of others determine one’s response, then there is no freedom, only reaction. Many spiritual orientations make you more responsible for your feelings and actions:

- “Very little is needed to make a happy life; it is all within yourself, in your way of thinking.” (Marcus Aurelius)

- “In the long run, we shape our lives, and we shape ourselves. The process never ends until we die. And the choices we make are ultimately our own responsibility.” (Eleanor Roosevelt)

- “Look at the word ‘responsibility’ – “response-ability” – the ability to choose your response.” (Steven Covey)

- “Man should not ask what the meaning of his life is, but rather must recognize that it is he who is asked.” (Viktor Frankl)

- “Do not let the behavior of others destroy your inner peace.” (HH the Dalai Lama)

Their essential message is that our perception of the world, and our reaction to it, are a matter of choice. And right attitudes and right actions manifest themselves not only in an improved internal experience, but also in relationships with others, including our relationship to the world. This deeper connection to self, others, and world was part of our definition of spirituality, the practical face of the spiritual journey.

What do “real people” say gives their working life meaning. In a survey from US consulting firm BetterUp55 conducted in 2018, today’s workers report that they find most meaning:

- “… where I’m trying to make other people’s lives better…”

- “…when I’m working to help others grow and see their potential…”

- “…when I am able to push my abilities to the utmost is the most fulfilling…”

- “…when my work revolves around helping others especially the disadvantaged and needy…”

This leads to a paradoxical situation. On one hand, meaning happens between our ears—and ultimately, only we can be responsible for the meaning we create. On the other hand, the employer, culture, work environment, job, and leadership can make it hard or easy to find meaning in a given job. Does the idea of personal responsibility for meaning-making give employers a free pass? Is it all “on you?” Of course not.

Here we find one of the most incisive criticisms of the whole idea of spirituality and business – the idea that finding meaning and purpose at work can be found if the individual works hard enough at it – no matter how oppressive the circumstances may be.

We saw that meaning and purpose can be found in the humblest of jobs: humans can reshape their narratives to a great extent. But, leaving all the spiritual heavy lifting to workers isn’t right—for them to enjoy a shitty job, they would have to become spiritual giants, master meaning-makers. There is also something deeply cynical about expecting someone who earns ten times less than you to get with the program and find the right attitude to make “loading 16 tons”56 meaningful.

The attitude of gratitude

“Cultivate the habit of being grateful for every good thing that comes to you, and to give thanks continuously. And because all things have contributed to your advancement, you should include all things in your gratitude.” ~Ralph Waldo Emerson

One attitude, though not by any means a uniquely spiritual one, is gratitude.57 Gratitude means being thankful, not just for specifics, as when a colleague does you a kindness, but generally, toward life, toward the people in it, and for circumstances (even those that seem harsh). As the saying goes, “Happiness isn’t getting what you want; it is wanting what you got.”

But like most valuable things in life, the attitude of gratitude takes practice and cultivation. The general “attitude of gratitude” creates an other- rather than self-orientation—an appreciation for what one has, rather than entitlement and grasping for what one lacks. As British author G.K. Chesterton said, “I would maintain that thanks are the highest form of thought and that gratitude is happiness doubled by wonder.”

Another way that the gratitude mindset is expressed is a “get to” rather than “have to” orientation. “Have to” people see a world with little choice, one whether they comply (grudgingly) with demands put upon them. “Get to” people may be doing the same thing, but with a different narrative—I “get to” do what I’m doing. This simple shift in narrative can be transformative.

Nietzsche, of course, had an even deeper take on gratitude. He suggested that true gratitude was being willing to live your life, just as it has happened, over and over again in eternal recurrence. (One of his signature ideas.) Only then, said he, when you accept all that has been, and are willing to live as such over and over, will peace and gratitude be found. “And then you will find every pain and every pleasure, every friend and every enemy, every hope and every error, every blade of grass and every ray of sunshine once more, and the whole fabric of things which make up your life.”58

One of the biggest obstacles to having attitudes at work (and in life) that create a better experience is the intrusion of negative thoughts. Everybody “knows” they should be grateful, everybody “knows” that they are the author of their own experience – but that “knowledge” can be of little use when the sniveling shipwreck of a human being in the next cubicle tries to take credit for your work, or you have to work past 9PM for the third time this week.

Everybody has thoughts that are not in the interest of the thinker. Everybody has impulses to do the wrong thing. Most of us ruminate a downward spiral of worry, fantasy, and resentment at least sometimes. How do we overcome negative thoughts, sometimes called the “itty bitty shitty committee” in your head? Let’s look at mindfulness.

53 You can find the ikigai and dozens of tools on purpose and calling in Reboot Your Career, a workbook that I co-authored with career coaching specialist Tim Ragan in 2016.

54 From poppy one-hit wonder group Bananarama and Fun Boy Three in the 1980s. Try to get that earworm out of your head now.

55 www.betterup.com

56 “You load 16 tons, and whaddya get? Another day older and deeper in debt. St. Peter don’t you call me, ‘cos I can’t go. I owe my soul to the company store.” (Folk song from 1947.)

57 Sometimes spiritual writers use the terms spirituality as if “all that good stuff” – humility, integrity, gratitude, passion, and conscience were uniquely spiritual. You can arrive at those attitudes through Humanistic psychology or many other ways. (No psychologist would take exception to the mentioned goodies.) We should not pretend that only spirituality, or only our own version of it is the only path to desirable human qualities – although our position is that the word “umbrellas” inner and outer work and includes those virtues and an ethical stance on life..

58 From The Gay Science, published in 1882.

To become a more innovative leader, you can begin by taking our free leadership assessments and then enrolling in our online leadership development program.

Check out the companion interview and past episodes of Innovating Leadership, Co-creating Our Future, via iTunes, TuneIn, Stitcher, Spotify, Amazon Music, Audible, iHeartRADIO, and NPR One. Stay up-to-date on new shows airing by following the Innovative Leadership Institute LinkedIn.

About the Authors

Paul Gibbons keynotes on five continents on the future of business, particularly on humanizing business, culture change, ethics, and the future of work. He is currently an academic advisor to Deloitte’s Human Capital practice – creating the future of change management He has authored five books, most prominently The Science of Successful Organizational Change and Impact, and he runs the popular philosophy podcast, Think Bigger Think Better. Those books are category best-sellers on Amazon in organizational change, decision-making, and leadership. After eight years as a consultant at PwC, Gibbons founded Future Considerations, a consulting firm that advises major corporations, including Shell, BP, Barclays, and HSBC, on leadership, strategy, and culture change. From 2015 to 2018, he was an adjunct professor of business ethics at the University of Denver. Paul is also a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts, a hyperpolyglot, has been named a “top-20 culture guru,” and one of the UK’s top two CEO “super coaches” by CEO magazine. He is a member of the American Philosophical Association, and the American Association for the Advancement of Science and lives in the Denver area with his two sons and enjoys competing internationally at mindsports such as poker, bridge, MOBA, and chess.