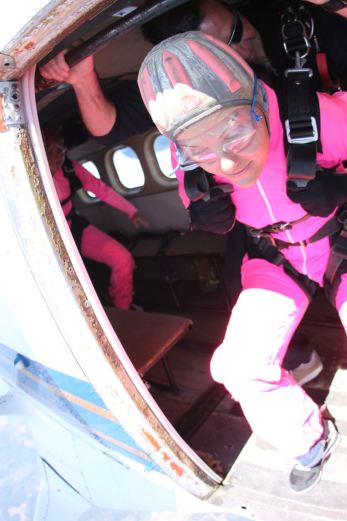

Photo by Andrew Longstreth

Want to be truly happy? Submerse yourself in something. Anything. As it turns out, we are happiest when we are focused. In the zone, going with the flow, in the moment, call it what you will. But when you are so focused that nothing else can intrude, then you find happiness.

Itâs that simple.

Maybe this is why I love to ski. I love to stand on top of a steep chute, drop in and focus only on the feel of the snow beneath my skis. Recently I skied a chute called Brain Damage at Crystal Mountain, where I work as a professional ski patroller. While the name of the chute is intimidating and the entrance is a no fall zone, in reality it isnât that difficult. Itâs enough to make me focus, but not so steep that I have to talk myself into it.

During those first few turns I bobbled a little, catching the inside of my right edge and chattering along the firm surface. I recovered before I even realized what had happened and continued through the narrowest part before traversing over to the wind-buffed Shankâs Chute and skied all the way to the bottom. I thought of nothing else but the skiing: the consistency of the snow, how it started like firm chalk and gave way to a soft, carve-able palate; the way my skis arced from one side of the couloir to another, the edges cutting tracks across the raised sides of the chute; the rock partway down the run that I hopped over gingerly and stopped thinking about the moment I passed over it.

When I got to the bottom, I didnât look back at my run. I just traversed towards the chairlift with a smile on my face. I was happy. For the few minutes it took me to complete the run, no other thoughts intruded. I did not think about work or the writing assignments in my inbox. There was no room in my brain for how I would juggle my schedule in the upcoming week, or the interviews I had scheduled or the millions of megabytes of brain space being occupied by all the things I wasnât doing at that moment.

Psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyiâs wrote the book on flow. In fact, his book FLOW: THE PSYCHOLOGY OF OPTIMAL EXPERIENCE has become the bible of all things zonal and flow-like, whether in action sports, playing the piano or becoming deeply involved in art. Being in flow, according to Csikszentmihalyi, provides us with optimal experiences, allowing us to live to our greatest potential. Flow moments have a few prerequisites.

- There is a balance between challenge and skill. You wonât feel in flow if youâre either a) scared out of your mind or b) bored. Brain Damage is anything but boring for me. Nor is it so difficult that Iâm unable to drop in without wetting my pants.

- Feedback is immediate. When I nearly fell at the top of Brain Damage, I received clear feedback. Pay attention. Get your skis underneath you, Stupid.

- The goals are clear. Thereâs no equivocation. The goal of skiing a steep chute is to get to the bottom with a modicum of style and all of your limbs intact.

- Action and awareness are merged. This is my favorite prerequisite. My personality vacillates between action and reflection. This is fine, but sometimes I get tired of analyzing everything. When I cannot think beyond the action of my next turn, Iâm happy. Truly, truly happy.

- Time is distorted. A few minutes can seem like an eternity, or hours can whiz by without realizing it. My run in Brain Damage, which lasted less than a minute, felt much longer. I can still recall it in its entirety, even without the help of a helmet cam.

- Self-consciousness and fear of failure fall away. For the length of my run down Brain Damage, I did not once worry if I was sticking my butt out too far. When I almost fell, I didnât consider the consequences or overthink my run. Instead I made the required moves to get back on track and continued down.

- The experience is autotelic, or worthwhile in itself. I didnât look back at my tracks, take photos or videos and I didnât post my run on Facebook (although yes, Iâm using it here on this blog as an example of happiness. That doesnât count). The doing of the thing–not the sharing of the thing–was worthy all by itself.

I, for one, can be in my head a little too much. It is these moments of intense focus that bring me back. As both a writer and ski patroller, I get to experience these flow moments as part of my job, when Iâm not over-thinking, Iâm simply a part of a larger picture. And that makes me very happy.

Kim Kircher is a professional ski patroller, author and talk show radio host for The Edge on the VoiceAmerica Sports Network. She has logged over 600 hours of explosives control, earning not only her avalanche blaster’s card, but also a heli-blaster endorsement, allowing her to fly over the slopes in a helicopter and drop bombs from the open cockpit, while uttering the fabulously thrilling words “bombs away” into the mic.

Her memoir, THE NEXT 15 MINUTES, takes the lessons she learned on the slopes as an EMT and applies them to her husband’s battle with bile duct cancer and subsequent liver transplant. Her articles have appeared in Women’s Adventure, The Ski Journal and Powder Online. She is currently at work on a book about risk and reward in action sports.

Her awards include the National Ski Patrol’s Purple Merit Star for saving a life and the Green Merit Star for saving a life in arduous conditions. Her memoir received the book award from the North American Ski Journalists Association.